1912 antedating

I couldn't find an origin but did find a slight

antedating of the 1919 letter.

The Railroad Telegrapher in

1912 printed a humorous poem/prayer. Here's an extract:

And if some "Ham" who sounds insane,

Should move me to say things profane

O stay my hand upon the key

And may I not get "H" for "P."

May I refrain to ope my door

And kick through it some tedious bore.

Who brings to me his half-wit kid

To be transformed into a lid.

A slight variation appears in Telephony of 1913, which gives

us the full text and quotes around jargon terms, and a

source:

Help ! Help !

Poetry will out, sometimes in the most unexpected

places and occasionally from unusual sources, says the

Los Angeles (Cal.) Times. One of the latest devotees of

the muse and one who has been creating considerable

comment around the Alexandria is little Miss Vivian

Ewing, Postal Telegraph operator in the hotel. After

months of viccisitudes and troubles caused principally

by the patrons of the little station in the marble

corridor, Miss Ewing evolved the following prayer to

assist her through her hours of toil:

Help me this day, O, Lord, to be

Kind and gentle with my key.

Help me earn my wage this day

And tempt me not to ask more pay;

And if some man who sounds insane

Should move me to hot things profane,

O stay my hand upon the key

And may I not make "H" for "P".

May I refrain to open my door

And kick through it a weary bore

Who brings to me his darling “kid”

To be transformed into a “lid”.

And may I gently treat the cranks

Who, after spoiling twenty blanks,

Fold up a lot of callow slush

And sternly bid me, “send it rush".

And when the clock points five to eight,

O, help me then to calmly wait

While some proud dad leans on the booth

And wires baby has a tooth.

In short, pray make me what I ain't,

An understudy of a saint,

That I may hold this job of mine

Till time gives me the "30" sign.

C. A. Shock, of Sherman, Texas, sent this to TELEPHONY

with the suggestion that variations might be rung on it

to make it apply to the telephone operator. So, “potes,"

sharpen pencils and have at it!

These are from snippets, so the years could be wrong, but

it appears to have been reprinted in other magazines

published between 1912-1914.

Lid operator

A lid operator, or lid, was

originally a novice operator, rather than any poor

operator.

Some quotations:

Telegraph Workers Journal,

1924:

Did you see Joe McKenua's lid? Some

plush. Bill Hartley is still ...

QST, 1925:

The "lid" operator can be told very

quickly when he makes a mistake. He does not use a

definite "error" signal but usually betrays himself by

sending a string of dots. The good operator sends "I ?"

after his mistakes and starts sending again with ...

QST, 1927:

When you have traffic and want to get it off, DO NOT

give it to a "lid" operator. If you

do, the chances are that It will die right there. Many

times I have become QSO with several stations in one

direction, with the intention of QSRlng, only to find

...

QST, 1928:

We plead guilty to "getting quite a kick out of"

operating our radio phone sets. The idea seems to

prevail that no one except a "ham", a "lid" or

a rank beginner even fools with phone.

Unfortunately this is true to some extent but there are

old ...

And:

... I flatter myself that I have become more than just

a lid operator. I hold a commercial

license, am an ORS and have made a fair showing in

traffic, and to you, OM, I owe a great part of my

success. You were my first schedule and I have tried to

...

And:

... gave several humorous anecdotes of his first trip

as a "lid" commercial operator on the

Great Lakes.

Telegraph Workers Journal,

1930:

Can it be a New Year's resolution, and that he is

starting at the bottom like an inexperienced

"lid"? Two nasty accidents occurred in "Mu"

since the advent of the New Year. Andy and Archie fell

off the booze-wagon. Nothing serious happened ...

However, Popular Science (1933) quoted

in the question is all about trade jargon, and includes an

English translation of "Telegrapher's Lingo". The full

description is of a novice, but specifically translates lid

as poor, showing the meaning is changing:

He uses a bug, but it runs away with him. As a sender

he's a lid.

...

Translated, this queer language means:

He uses a semi-automatic key, but keeps it adjusted at

a speed greater than that at which he can manipulate it

properly. As a sender of messages he is poor.

It goes on to praise him for being able to receive at the

fastest speeds and for never interrupting. (It also

explains what "30" means, as mentioned in the 1919 poem.)

Sitting on the lid

This may be unrelated, but I'll include it on the off

chance. The Railroad Telegrapher included

reports of union members' work situation ("In 1920, there were 78,134

telegraphers on all railroads represented by The Order of

Railroad Telegraphers. Membership in the union had

peaked."). Some of these would include the phrase "is

sitting on the lid". Here are some examples.

From the preceding 1913 Telephony:

I. S. Johnson and Leo Smiddy are working extra there,

while Bro. Bob Fountaine sits on the lid.

The Railroad Telegrapher in

1911:

Bros. Packard, Wilson and Nickel sat on the

lid while Bro. Hook attended the TOI'0.'ll0

[?] convention and took a trip through the East. He was

relieved by Bro. _l. L. Druley, from the \'abash [?].

And here:

... rear brakeman on the division correspondent's

motorcycle for several miles. I introduced him to the

high and low crossings at a speed of 30 miles per, when

we stopped he had both legs wrapped around the gas tank,

and was settin' on his lid.

And here:

Mr. John Dalzell, Chairman of the Rules Committee, sat

stubbornly "on the lid" and refused to budge.

He believes that free trade in labor is the safest

bulwark of tariff protection for employers.

The Railroad Telegrapher, 1914

(date verified):

Two operators taken off at Merino, making it a one-man

station, with Bro. Johnson on the lid.

Bro. Doherty to second Brighton, bumping Bro. Baker to

second Carr, vice Bro. Seeley bumping Bro. Rotenbaum;

Dent nights to the extra list.

I'm not entirely clear what this sitting on the lid

refers to, but for the work reports, I get the impression

it's similar to sitting on the bench, being held

as reserve.

One of these is not a work report but a political report:

"Mr. John Dalzell, Chairman of the Rules Committee, sat

stubbornly "on the lid" and refused to budge."

This has a political meaning, according to A

Desk-Book of Errors in English (1906, 1920) by

Frank Horace Vizetelly:

lid: A slang term for cover, hat,

etc., used especially in the phrases keeping

the lid down, sitting on the lid, political

colloquialisms for closing up places of business, as

pool-rooms, saloons, etc., or keeping a political

situation in control.

This fits for the stubborn chairman of the rules

committee, and speculating, perhaps this "keeping control"

sense was applied to reserve workers patiently waiting

their turn. Or perhaps the union work reports are telling

us those workers were taking care of union business and

keeping their local situation in control.

In any case, the political phrase "sitting on the lid"

originated or was at least popularised by President

Theodore Roosevelt when describing Secretary of War, William

Howard Taft:

Taft as Secretary of War became the administration's

"trouble shooter" at home and abroad. During the years

between 1904 and 1908 Taft had direct charge of the

construction of the Panama Canal. Roosevelt considered

Taft one of his most valuable assets, so able was Taft

that Roosevelt felt free to leave the capital whenever

he wished, because he had "left Taft sitting on

the lid." As Roosevelt's personal emissary

Taft was sent on many diplomatic assignments.

The New York Times, April

1905:

It was suggested to the president that things would go

along in a smooth manner, even if he was absent.

Oh, things will be all right," he said. "I have left Taft

sitting on the lid keeping down the Santo

Domingo matter."

Roosevelt commented in a May 1905 letter to his son:

Yes, I have been much amused with the cartoons about my

remarking that I had "left Taft sitting on the

lid". Some of the cartoons about the bear and

wolf hunting have been really funny.

A The Evening News of 1922

commented:

This phrase went around the country at the time, and

the fact that Mr. Taft's physical weight was such that

we all had a feeling that if he were sitting on

the lid, the lid must be geld down pretty

firmly, undoubtedly had much to do with the success of

the great phrase-maker's remark at that time.

More speculation: "sitting on the lid" was a metaphor for

"sitting on a hat" meaning "keeping control" and the

meaning passed to "sitting as a reserve on the bench".

Operators sitting in reserve are often novice operators,

or "lid operators". A lid operator was then originally a

novice worker, and as novice workers would make more

mistakes, the meaning then changed to refer to any poor

operator.

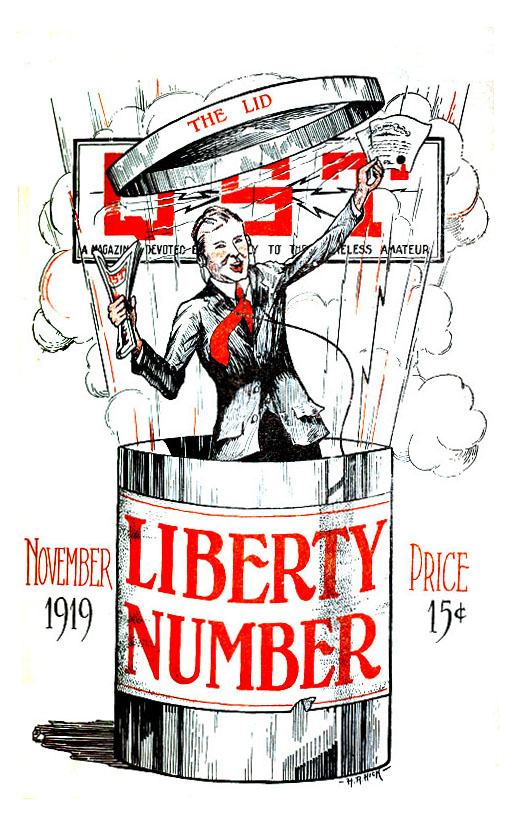

Finally,

nearly one year after the armistice, a breakthrough: A single,

tacked-on page, after the end cover of October QST, a hastily

added special announcement proclaimed: “BAN OFF! THE JOB IS

DONE AND THE A.R.R.L. DID IT. See next QST for details”

Finally,

nearly one year after the armistice, a breakthrough: A single,

tacked-on page, after the end cover of October QST, a hastily

added special announcement proclaimed: “BAN OFF! THE JOB IS

DONE AND THE A.R.R.L. DID IT. See next QST for details”